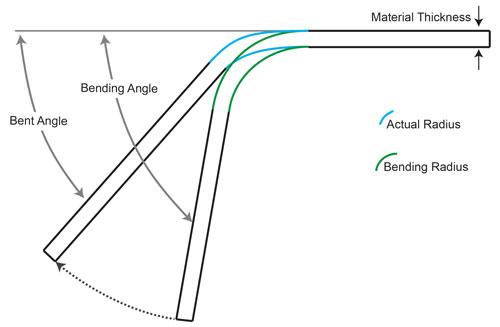

To a press brake operator, a bending angle is different from a bent angle, and it all has to do with that ever-present forming variable: springback.

Springback occurs when the material angularly tries to return to its original shape after being bent. When fabricating on the press brake, an operator will overbend to the bending angle, which is angularly past the required bent angle, compensating for the springback. Overbending to the bending angle allows the desired bent angle to be attained when the part is released from pressure.

The tensile strength and thickness of the material, type of tooling, and the type of bending all greatly influence springback. Efficiently predicting and accounting for springback are critical, especially when working with profound-radius bends, as well as thick and high-strength material.

The Science of Springback

Why exactly does springback occur? There are two reasons. The first has to do with displacement of molecules within the material, and the second has to do with stress and strain. As the material is bent, the inner region of the bend is compressed while the outer region is stretched, so the molecular density is greater on the inside of the bend than on the outer surface. The compressive forces are less than the tensile forces on the outside of the bend, and this causes the material to try to return to its flat position.

The elastic zone is where the material is moved but not bent; when the stress is released, the material returns to its original shape without any permanent deformation. When enough force/penetration is applied, the material reaches its yield point, and permanent deformation of the metal begins to occur.

The air forming zone shows that when the press brake exerts pressure on the sheet, the metal begins to bend. During air forming the workpiece springs back slightly when released from pressure, as it attempts to return to its original shape. The amount of springback that occurs is a property of the material and radius. In common materials, if the material thickness and the inside radius are equal, the springback is usually 2 degrees or less in common material types. However, springback increases dramatically as the inside radius of the bend increases in relationship to the material thickness. Note that new high-strength steels have a greater amount of springback as compared to basic mild steels, general grades of stainless, and many aluminums.

In the bottoming zone, the material contacts the bottom of the die, angularly overbending an amount equal to the springback, and then experiences a brief stage of negative springback—also known as springforward—as the pressure is increased.

As the force continues to increase, the bending process enters into the coining zone, where an overbend happens for a brief moment before springforward occurs again. Ultimately, the springback and springforward forces average out, becoming the process we know as coining. With this process, the final product has no springback remaining. That’s because in a coined sheet metal part, the punch tip penetrates the neutral axis while thinning the material at the point of bend, realigning the material’s molecular structure. At this point, the material’s integrity is pretty much gone.

The original artical's link:https://www.thefabricator.com/thefabricator/article/bending/bending-basics-the-hows-and-whys-of-springback-and-springforward

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder